One Week Down.

22.3 miles down, 414.2 to go.

That’s my longest week in a while. I really dropped off my training in June and July, from a running perspective. Obviously, while I was triathlon training, I took some runs off my calendar and added some biking and some swimming. As a result, my total miles this year, compared to last, are way, way down. In fact, through the end of July, I’ve run 200 fewer miles than the same period last year.

On the other hand, in the entire calendar year last year, I rode 523 miles. Which I’ve already surpassed this year with five months to go. And I’ve swum some 10 kilometers this year, compared with about 1 last year. And in both years I’ve maintained a good gym presence, and done at least weekly strength training, and usually twice a week.

But the biking will drop off from here – and a lot of it won’t get recorded because I’m riding to and from work every day but not wearing my watch for that. So I could be adding almost 30 miles a week I won’t be recording. But that’s at the cost of walking. So, higher heart rate but lower calories burned. I don’t know what the effect of that tradeoff is, and I’m not convinced anyone does. I’m sure it’s idiosyncratic to the individual.

My knee is still barking at me, and this weekend’s long run was tough, but I did it at a fair clip. 10 miles at a 10:39 pace. It was cooler and drier, which helped. 65 degrees at the start of the run and only about 72 at the end of it. But I was still drenched in sweat, and the last two miles were unpleasant. After my triathlon, I rested for a week. And before it, I tapered for a week. Which means I basically took two weeks off with a big lift in the middle.

I needed that from a mental perspective: it’s a grind getting out there day in and day out. Some kind of exercise for at least 40-45 minutes six days a week. I generally get in somewhere between 7-10 hours of exercise a week, which seems like it ought to make me a lot fitter than I am. Just goes to show how hard it is for me to make improvements.

But I have been making them. I have done four chin-ups (palms in) and I even did two pull-ups (palms out) this weekend. That is a strictly objective measure of my improving strength. I hadn’t been able to do a real pull-up since junior high. Now, at 42, I did two of them in a row without putting my feet down in between. That feels really good.

I don’t get the same sense of accomplishment from lifting a heavier weight as I do from running a longer race. Races just take more. But I do like seeing the improvement from my strength training, and I feel strongly that it contributes to my running. But mostly, all of it contributes to my overall health and wellness.

My blood pressure is good. My other blood numbers are pretty good. And my A1c is staying below 5.8. I’m in pretty good shape, and while I could weigh less, I look good in a suit and feel fit when BB and I go hiking in foreign cities wearing heavy packs. That’s what I want out of life. So it’s going well.

This Year’s Training Plan.

I am, dear reader, sloppy and undisciplined in most things. By which I mean, I do the minimum I need to do to get by and accomplish my goals. Often my goals are fairly lofty, and thus require a modicum of effort and discipline to achieve, but even then I do only what I think I have to do to succeed and do not go the “extra mile” to thrive and truly excel. This is why I’m a half-way decent pianist, for example. I’m good enough for me.

And that all applies to running too. If I did track workouts and intervals and hill training and blah blah blah I’m sure I would be much faster than I am. But that all requires a lot of work. And since my satisfaction comes from finishing, rather than from maximizing my speed over long distances, I don’t do those things very often. Certainly not often enough for them to have performance effects. I have never done a track workout.

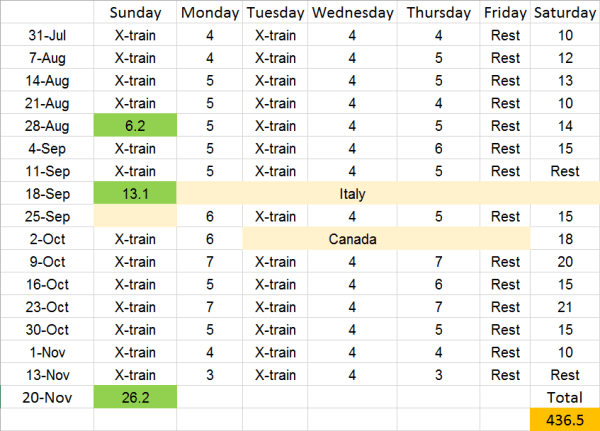

So I designed a nice, undisciplined, sloppy marathon training schedule that will get me to the end, and allow me to complete another 26.2 mile run in late November.

As I wrote before, this is about 65 miles less than last year’s plan. Mostly because I don’t have 3 mile recovery runs on Sunday. I don’t know what kind of running I’ll get in when I travel, but I’m not going to knock myself out about it. Rome is hilly. To hell with that.

But I know that this plan will get me to the end, and have me ready to run 26.2 miles on the 20th of November. I don’t know how fast, and I don’t know how much it will hurt. But I know I can do it because I’ve done it before. And I know that when I’ve worked hard, I’ve improved. I expect to improve again. But if I don’t, I don’t. That’s ok. I just want to finish and collect a medal.

And I think maybe I start looking for another triathlon to compete in…

Marathon Training Day One.

Well, day one is in the books with a fast-ish (for summer) four mile run in a touch less than 40 minutes. A 9:53 pace that felt fast to me. I run much, much slower in the summer. The heat just saps my strength, and my legs feel wooden and dead. Once the cooler weather comes back, I’m sure I’ll have no trouble doing this run in the 35-37 minutes it usually takes me. But for today, I’ll be happy with it.

I had to abort my long run over the weekend. The humidity and a foul mood worked against me from the beginning and I just quit after 2.8 miles. Walked home in a funk. My mood hasn’t been great these past few weeks, and I suppose that’s understandable given everything going on, but I’m still just feeling grumpy and uckled.

I’ve worked out a training plan that is about 65 miles shorter than last year. When training to finish, rather than for a time goal, and when you’re as slow as I am, all those miles pile up. If I could run seven minute miles, I could put in 50 mile weeks and really train for pace. But when my top speed on a short run is about 8:30, and on a longer run 10:00, well, putting in even a 40 mile week takes a long, long time. So I shaved some distance.

My hope is that it keeps my legs a little fresher, doesn’t leave me constantly starving, and helps me run the 26.2 a few minutes faster than last year. Last year, we came in right at an 11:25 pace for the marathon. This year, if we broke 11 min/mi, it would represent a large increase in fitness and time. That feels like a very achievable goal.

But as always, my goal is to finish, with BB beside me. To run the whole way. To cross the finish line uninjured, and then eat a pile of pancakes.

Ashamed of Half My Country.

I often think about a conversation I once had with my sister, Aimee. She’s always been liberal leaning towards socialist, and I was, at the time, very conservative*. Despite what the left thinks, privileged people on both the left and the right are generally concerned with and troubled by the plight of people less fortunate. But they have different ideas about how to resolve it. My sister’s comment was that “Liberals and conservatives resolve their cognitive dissonances in different ways.”

That’s true, I think. Painting with a very broad brush, the liberal approach to accepting privilege is guilt, while the conservative approach is entitlement. Liberals feel that they don’t deserve their privileges and thus must either eschew them or work to provide them for others less benefitted. Conservatives feel that they do deserve their privileges, because they’ve worked hard for them, and thus want to make a world where everyone’s hard work will enable them the same access to privilege.

I’m not going to argue about which vision is more accurate or better or whatever. I used to fall squarely into the conservative camp, but I’ve come to see too many instances where hard work avails nothing. And my own research has demonstrated that clandestine biases are more powerful than they seem. Nevertheless, I haven’t swung entirely into the guilt-ridden liberal penitent camp either.

It used to be that the major parties lined up fairly well with these visions, and the country would pendulum back and forth between them with predictable periodicity, gradually trending a little further left, as most wealthy countries do. As a result, there have been many major social gains for the left in the past few decades, culminating in real progress toward comprehensive freedom. Marriage equality, for example, has extended massive rights and privileges to groups formerly proscribed from them.

Lately though, the parties have drifted in a way that cannot be described on an axis. The GOP has embraced an openly xenophobic agenda, and an isolationist one, and a bigoted one. This is not conservative. If social conservatives were dismayed by hedonism, they would embrace the recognition of family structures among those they consider hedonistic. Instead, they are merely angry at others enjoying their own privileges.

Conservatism has always, heretofore, embraced the immigrant experience. The idea that anyone can come to America, and work for their own fortune. The Melting Pot is the conservative ideal: that people of all the world can come assimilate to American culture and thrive. Liberals, today, by and large reject the Melting Pot metaphor, preferring a multi-cultural ideal of many traditions co-existing peacefully. Both visions are defensible. What is indefensible is sealing the borders.

There is blame to go around here. It is unsurprising that a leftward lurch has a backlash. It is unsurprising that a mendacious media which hyper-saturates us with violence and terror – which are, in fact, quite rare – foments isolationism in some. It is unsurprising that decades of political rhetoric where every opponent is caricatured as a violent fascist or conspiratorial communist has left us vulnerable to the rise of a candidate who is actually a fascist.

But the chief blame of any bad act lies on the shoulders of the person who commits it. The GOP has nominated the foulest political figure in American history. They and those who vote for him are the ones who bear the brunt of responsibility should his bleak vision of America, and the ghastly consequences of his leadership, take hold.

I have a lot of difficulty with Hillary Clinton’s fiscal and economic policies. I think many of her visions are too expensive and too mollycoddling of the electorate. Though I find her social policy to be basically appropriate, and actually more conservative than the GOP’s in many ways: embracing of the immigrant, pro marriage, etc.. As a person with a lot of conservative positions, pulling the ballot lever for Hillary Clinton will be chalky, I suspect.

But that’s the lever I will pull, and I’ll do so without the first shadow of reconsideration. We face, right now, the greatest threat to America since the Civil War. We have, simultaneously, among the most qualified and least qualified candidates ever put forth for the position of President. And among the most capable, and least capable.

Hillary Clinton will be a faithful steward of this nation and its laws, even if I am not entirely thrilled by the direction she’ll point the ship. But Trump? He doesn’t know how to steer, but he’s determined to run aground regardless.

__________________________________

* I’ve always been pretty conservative economically, and I remain more conservative than most of my academic colleagues today. Which is a little like saying that I’m not as dry as Death Valley.

Resting.

Since finishing the triathlon, I’ve worked out only once. I suppose that’s not that much of a slack off, after all, it’s Thursday morning, and so that means I’ve rested two of three days. But my plan is to rest again today. Maybe tomorrow too. I’m tired, and I’ve been training hard for races almost nonstop for about two years. I still have three races on my schedule for this year, possibly four if BB and I add a 15 km race in DC we saw that looks fun.

Racing is awesome, and I enjoy it and I love collecting medals. I love the accomplishment and the feeling of fitness and connection with BB I get from it. But constant training is wearying too. In addition to the physical toll, it can be mentally exhausting to never take a break. Burn out is real, and insidious. It’s time for me to take a week or so off so that I don’t burn myself down and feel like the fall marathon is a burden, not a joy.

BB and I set a goal for ourselves to remain “half-marathon fit”. Meaning, any morning we wake up, if we want to, we should be able to call in “sick” to work and go run 13 miles. We’ve done that. What an amazing thing, really, too. Just the ability to go and run for two hours without stopping feels incredible, and like an enormous privilege. Similarly, I am now capable of a three hour triathlon, covering almost 30 miles of swimming and cycling and running, without stopping. Unbelievable to me. It used to be impossible for me to walk 200 yards up a steep hill without resting in the middle.

But even though I am amazed at what I’ve been able to do, I can still get exhausted and feel overwhelmed. I need to take a short break before committing to my marathon training. Marathon training is awesome, but monotonous. Day after day after day running for hours at a time, putting in 35-40 miles on the long weeks, and suffering all of the various little injuries and ailments along the way.

I’ve worked out a plan with a little less in the way of weekday miles, and a little more cross training this year. We’ll see how that feels. As usual, my goal is to finish. But I’d love to set a new personal record too. Which I think will be possible, and even likely. We’re not going to stand around for two full hours ahead of the race start, our feet getting swollen. So it ought to hurt less.

But before all that, before the race, the training, the effort, and the agony, I need a rest. I spent months training for a big thing. I did the big thing. I got the medal. I’m proud. And I’m tired. So I’m resting.

Mental Illness on Display.

At the Democratic National Convention last night, several speakers talked about their history of struggles with mental illness. Pop singer Demi Lovato, especially, gave a compelling and heartfelt talk. Aside from being an inspirational figure on the world stage talking about her personal story, it’s a proven fact you can lift 30% more weight at the gym while listening to her song “Confident“. A former mayor of Boston spoke about his alcoholism.

I never know quite how to feel during these personal testimonies on television. Lovato’s speech had tears in my eyes. It was courageous and moving. Her personal troubles, as a celebrity, had been well-documented. And they’re quite similar to my own. Addiction, eating disorders, and self-harm. In addition, Lovato suffers from bipolar disorder, a condition I have no personal relationship with.

It is good to see people who have recovered go forth and say that recovery exists and can be accomplished. The need for alcoholics to hide our addictions for fear that even in recovery we would be mistreated is no longer quite so acute. Though we still suffer stigmas and misunderstanding, it tends to be of a softer sort. Being told “good for you” is grating, and minimizing, but it’s not nearly as bad as being told, “you’re fired,” because your boss doesn’t believe your recovery is stable.

But I fear that there can also be something self-aggrandizing and ego-feeding about these public testimonials. Recovery from addiction requires us to defeat our own out-of-control egos that tell us, even in our darkest moments, that we are the only thing that matters. So much so that it can drive us to suicide: nothing beyond the self exists, so it doesn’t matter if we end the self.

I have a toxic ego that I am constantly battling. During the difficult final 5 km of my triathlon, I kept telling myself, “I’m not special. There’s no reason I shouldn’t hurt like everyone else.” I need to deflate my ego constantly in order to maintain my recovery. My ego leads me to inflate my importance, to think I’m in control. As soon as I think that my recovery is about my own efforts, I am lost.

Don’t get me wrong. I work like hell at it and I have pride in those efforts. Recovery is a parade of contradictions. But they resolve themselves into a few simple concepts. I cannot recover alone. I am not God. Forces bigger than myself must be mustered for me to have hope for a normal life. And I hope that what I write here is helpful to some, and I believe it has been. But I can’t cure anyone. And I can’t take credit for anyone else’s recovery.

My addiction is not a lever to public acclaim. Nor is my anonymity a cloak of invisibility. I hope that those who speak publicly help people. And I know the courage it takes to stand up and say, “I am ill, and that sometimes makes me feel weak. But I have recovered, and that hope is available to everyone.” It is moving to see that strength from people – especially those who have much to lose.

Because that’s the truth of it. I am ill. My illness led me to make many terrible decisions. I harmed people I can never repair. I gave up many things I’ll never get back. But I have recovered. I make better decisions, most of the time, now. I harm people less frequently, and I repair the damage I do promptly when I can. I share my disease and my recovery from it.

But I don’t think you’d find me on a stage, if someone offered one to me. I could far too easily make it about myself. My life. My story. And I do not doubt that could lead me rapidly back to the abyss.

If They Knew How Far I’ve Come.

I did it. Today I completed the New Jersey State Triathlon, and I did it faster than I dreamed I could. I’m incredibly proud of finishing, and even prouder of my time. A long, difficult morning in the sun and heat, starting with a practice swim. My Olympic Triathlon race recap:

I went in the water for a practice 200-300 yards, because naturally I had forgotten my goggles and had to buy new ones at the expo. And they started leaking immediately. I kind of panicked. I didn’t think they’d work, but then I found I could give them a “burp” like tupperware, and they didn’t leak. I was briefly concerned that I shouldn’t have swum so far to practice, but it was what it was.

My swim wave was one of the later ones, so BB and I hunkered down on a hill and waited and watched. When my time came, I herded into the water with about 120 other men aged 40-44. The announcer howled and off we went in a surge. It took me a few minutes to get my bearings, but my goggles held and I found a rhythm. I took a line a little off the buoy string and sighted every four or five strokes. After about 700 meters, my lower back hurt a bit, but you can’t stop and stretch in the water. I swam.

It was crowded and I was kicked and slapped several times, but I did my fair share of kicking and slapping too. The course wasn’t difficult to navigate, and I found myself keeping a good time. Eventually, the faster swimmers from the group behind me overtook me, but I made the beach in 39 minutes, far faster than I expected to, or had practiced.

The transition was pretty straightforward. There weren’t many bikes left in my section, meaning exactly what I’d expected: I was slow (even at my unexpectedly fast pace) for my age group. I dressed, threw on my helmet, slugged down my gatorade, and ran my bike to the mounting line. I swung my leg over and started riding.

My race plan was to push harder on the bike, so that I could start the run earlier, and hopefully stave off some of the brutal heat (it was 84 degrees when I left the water). I found a good stroke, and set my watch to show my average speed. I found I could keep it right around 18 miles per hour and felt really good about that. It was a flat course with only a few shallow, short climbs.

I worried about infractions and drafting a bit, but found it wasn’t that big a deal. I was able to pass when I needed to pass, and some people rode past me like I was standing still. I started to tire a bit by mile 14 or 15, but my legs stayed strong even though they were tired. The 20 miles took me about 65 minutes, a full five minutes less than my optimistic pre-race plan of 70.

I cruised into the transition again, realized I’d forgotten to take on salt after the swim and slugged down a couple of salt stick pills. I had taken on about 200 calories of peanut butter/fig bar on the ride, along with 20 oz of gatorade. I rushed out of transition and realized I’d forgotten my bib. I spun back around and tied it on, and got out on the run course. Each transition was between 4 and 5 minutes.

The run. It was 86 degrees when I started. Not too humid. And the run course had periodic areas of shade. Lots of support. Lots of kids who were glad to heave ice water at me as I ran by and shouted, “HIT ME!”. My legs felt like jelly, but I got myself going and kept it up. My first mile was a 9:44, but I didn’t keep that up. I slowed down throughout the course, finally turning in a 68 minute run that hurt, and never turned into feeling like a real run. Just a stiff-legged shuffle that got me to the end.

As I came in to the finish, I started to tear up a bit. The announcer called my name, and I thought, “If they knew how far I’ve come.” I’ve come a long, long way. From chronic, suicide drunk, smoker, obese, to now a marathoner and triathlete. It’s been a long journey, and I have further yet to go. Which made this tweet from my friend Katiesci all the more poignant to me:

@Dr24hours So awesome!! You’ve come so freaking far. Congrats!!

— Dr. Katiesci (@katiesci) July 24, 2016

This, dear readers, is how you acknowledge the effort of a person in recovery without stigmatizing. Without that saccharine condescension inherent in “good for you”, that tells alcoholics in recovery that they ought to be incompetent, that their achievement is only adequate for someone with massive disadvantages inherent to their selves and capacities. This is the right way to congratulate us: we have come far. We had a long way to come.

I was congratulated at the finish line, three hours and three minutes after I started, by a number of people who I’d spoken to, who knew it was my first triathlon. They bumped fists with me and told me I’d run a good race. If they only knew how far I’ve come.

BB ran about as far as I did, racing all over the course to show up and cheer for me. And even hugging me at the end even though I was drenched in sweat and lakewater. And then we headed home. I’m home now, and ready to sleep. I’ve earned it. I’ve come a long way.

On Being the Exception.

Recovering from alcoholism in Alcoholics Anonymous is very straightforward. Don’t drink. Go to meetings. Do the steps. Keep these things up, and you’ll make it. But recovery is hard. Doing those steps requires a lot of work, willingness to look at yourself and see how you cause your own problems. Refusal to be a victim of others. Acceptance of responsibility. Action and accountability. Everything that society tells us we shouldn’t have to do: we’re all perfect the way we are; your problems are someone else’s fault. But if you can embrace the ego-deflating process of self-searching and seeking required, you can recover from alcoholism.

Let’s be honest, recovery is also unlikely. As I have written many times: most of us die. Most of us die without even attempting to recover. But most of us who do attempt to recover also die of alcoholism. Because doing the work required is hard, unending, and requires a complete renovation of your life style. Including your associates, and sometimes family. It seems that most people can’t do it. Every week I see new faces in meetings that I’ll never see again. Some of them may recover elsewhere. Most of them die.

It is a peculiar paradox, recovery. We know it can happen. It does happen. And yet we also know it won’t happen for the great majority. I’ve been in recovery now eight and a half years, and compared to some of the men I see every Wednesday that makes me still a baby in recovery. I know plenty of people with 30, 40 years of recovery. People who will die sober of something else. I hope to be one of those. I feel like I’m on a good path, but it is not a path that ever leaves the woods. I am never out of danger. But I know how to minimize it.

When it comes to recovery, I am already an exception. Just deciding to try makes me one of a few. Finding the willingness to work the program makes me one of fewer. Being able to maintain a program makes me one of a very small number. And I want to be clear. I do not believe it’s me. I do not have the power to do these things in myself. I am not very spiritual these days, but I have no illusion that I am the author of my own recovery. I can not do this. I am buoyed by forces stronger than myself.

I had a conversation with my sister (in which neither of us got to really elaborate on our ideas, so don’t blame her for any of this) that was about weight loss more than recovery, but I see them in similar lights. She argued that it’s not fair to tell people they have to be the exception – that if very few people can lose a lot of weight and maintain that weightloss, that it’s not ok to tell people that it’s a goal worth pursuing. I disagree.

I think it’s perfectly fine to be honest with people and say: the path you’re embarking on is incredibly difficult and few people are successful in the long term. It can be done, but it is out of reach for most. We don’t know ahead of time who can maintain it and who can’t. But we do know that for some few people, there’s a better life to be had if that’s what you consider to be a better life (whether that’s weightloss or recovery, or whatever).

Behavioral and lifestyle interventions are presented badly. We teach short-term drastic changes. Lose the weight on this crash diet, and then you’ll be able to go back to eating pizza. Don’t drink for a month, and you’ll prove you’re not an alcoholic. Train for a 5k and you’ll be fit forever. It’s bullshit. To see change – lifelong, difficult, lifestyle change – you have to make lifelong modifications to your behavior. And that’s fucking hard.

Lots of people can’t do it. The people who can and do are not “better” than people who don’t and can’t. We don’t know what puts people in one group or the other, and I promise you we never will. But that also means you don’t know which group you’re in until you try. Really try. Dedicate your life to it. Make the change. Be the change. Live the change.

And to really make change, I exhort you to recognize that you probably can’t do it on your own. I couldn’t. I didn’t. We need help. Groups of people who do what we’d like to do. In Alcoholics Anonymous, we say: if you want what we have, and are willing to go to any length to get it, you are ready to take certain steps. The same is true for weightloss and health: if you want it, go find people who have it, and then join them in doing what they do.

Now, I recognize that weightloss and alcoholism are not identical, but I think they share more than a lot of people want to admit. To intervene for either, lifelong, difficult, painful, unrelenting lifestyle changes must be made. I know because I’ve done both. I know how hard it is, and I know how unlikely it is to succeed. Because I’ve watched friends who are smarter than me, stronger than me, and better than me fail at both.

But it is not impossible. It is only very difficult. And in life, isn’t it the difficult things that are most worth doing? Being a concert pianist is unlikely and difficult too. And lots more people have the talent than succeed. Because the crucial part of it is the discipline. That’s the thing. It’s getting up each day and deciding that yes, today I will do the difficult thing too. I’ll run. I’ll cook. I’ll sweat. I’ll go to a meeting. I’ll write about my alcoholism. I’ll call my sponsor.

Be the exception.

At this Point, it’s about Surviving.

I keep hoping the prevailing winds will change. I don’t think they will. I keep hoping that “showers” will show up on the forecast. Or at least, “clouds”. Hope seems futile. Sunday, July 24th, 2016, in Princeton, New Jersey is going to be one of the hottest days of the year, under a brutal, glaring sun. My sole saving grace appears to be that it will not be humid.

It will be about 80 degrees when I hit the water. 85 when I mount my bike. And tipping 90 or 92 by the time I head off on my run. It is going to be dangerously hot for me, on my first triathlon, attempting to cover 27.1 miles of ground in a little less than four and a half hours.

I don’t really know what to do. I’ve trained for heat, some, but there’s no way for me to teach my body to endure this kind of heat for a long time. I am just going to have to do the best I can, recognize my limitations, and accept that crossing the finish line alive – however slowly I go, is my victory.

That probably means walking a great deal of the run. Which means going very slowly and flirting with the time cutoffs. Which means I need to make up some time on the bike and the swim. I don’t know if I can do anything about the swim. A smooth steady pace is the safest and strongest for me.

Which means the bike. The nice thing about riding a bike is you get a breeze. So I think I’ll be able to push a little on the bike, pick up a few minutes, and leave myself plenty of time to walk/jog the 10 km. If I can average a 3:30 mile, the ride will take me 70 minutes. Throw in an hour for the swim and two transitions, and I have almost two and a half hours for the run.

I will wear my GPS watch, and try to capture my race with it. But I might forget or it might not sync up rapidly enough to use during the race. That’s risk. I don’t have a GPS track of my marathon, because I was using my phone at the time and its battery died. I like having them, but it’s not crucial. The real value of my watch is that I can use it to monitor my heart rate. If I’m pushing past 185, I need to slow down until I cool down.

We have a hotel. I have my bike. I have my suit and my shoes. I know how to swim. I know how to ride. I know how to run. I know how it feels when I can’t keep pushing. I know how to push through pain, and recognize injury. I can make it. I’m gonna make it. Right?

Finding My Own Path.

I am not living the life that was planned for me. Upon showing some scholastic agility when I was a child, I began being told that I was fit for great things by a lot of people. Parents, teachers. I was a bright child, and I had accomplished progenitors, at least on my mother’s side. I was told from an early age that I would be following the path laid for me by one of two men, either my grandfather, the civil engineer and real estate developer, or his brother, the professor and mechanician. For some reason, their other brother, the physician, was left out.

But I never could quite live up to those expectations. I was good at math, but I wasn’t a prodigy. By the time I went to college, I wasn’t too keen on pursuing civil engineering anymore, a feeling reinforced by my mediocre accomplishment in those classes. I switched over to systems engineering in a fit of tears, certain I was destroying my mother’s dreams for me. She surprised me, supporting the move and being pleased I’d found a path I enjoyed. I think we’d have had a different conversation if I’d chosen, say, theater.

But in systems, I was still considered something of a high-potential asset. My advisor pushed me on toward a doctorate. He offered me a position as a graduate student in his lab. Columbia University, the school my great uncle taught at, did the same. I was offered a position before I ever even applied for one. The took me to a vast computer lab and told me it would be “mine”.

I had, apparently, chosen my great uncle’s path toward professorship and academic achievement as an adult. I accepted my undergraduate advisor’s position, and went to work on a doctorate. A year later I decided to quit. A year after that I decided to un-quit. I passed my qualifiers, barely. I had begun drinking in earnest now. I slowly made progress on my course work and research, gradually sinking further and further into suicidal alcoholism.

Just as I was ready to abandon everything again, my advisor wrestled a dissertation from me, and ordered me to defend it. I didn’t want to. I knew it wasn’t any good. But I did it. And I passed. And then I just sat down. I was ostensibly trying to start a consulting company. But I wasn’t really. I had enough money to live on, because I was highly privileged. And so I was unemployed, drinking as hard as I could, and married to a woman with a child who both deserved better.

No one believed in me anymore. Least of all myself. Not my wife. Not my stepson, not my parents, not my advisor. I didn’t even apply for any positions. Not that I’d have gotten one. I started a business and pursued nothing. I drank and drank and drank. Everything was falling apart. Until the day came that I couldn’t anymore and I had to let it all come apart and I left for inpatient rehab.

I was offered a job while I was in rehab, as a technician for the chief of staff of a small local hospital. At less than half of what I thought I “should” be making. But the good thing about alcoholism, and recovery from it, is that it makes you humble. I was willing to do anything to return to a state of dignity and value. So I took that job. It started after a bunch of paperwork snafus when I was about six months sober.

I was suddenly able to contribute. It was difficult and disorienting. I wasn’t good at real-world work, and my boss was sort of nutty. But I made it. Within 18 months, my salary had more than doubled, and I was made a principal investigator. Suddenly I was doing work I understood, enjoyed, and was good at. I learned a lot of things very rapidly, like how to write for medical journals and grantsmanship.

I got a couple of grants. I published a couple of papers. I did some things wrong, not understanding the IRB process and the internal rules about submitting manuscripts. I was censured, but not harshly. Luckily, my research doesn’t expose any human subjects to risk of harm. But eventually, my funding ran out and I needed to find a new position. I moved out to MECMC, and started building a different kind of enterprise.

Now I’m doing work I care about at an institution I love. I’m not a professor. I’m not a civil engineer. I do mentor students from time to time. I publish work that’s of no interest at all from a theoretical perspective, but is useful for learning to improve hospitals and the care they provide. As I’ve said many times: I’m not interested in convincing other engineers to do what I do the way I do it. I’m interested in convincing physicians and administrators that what I do exists and is a good investment.

I disappointed a lot of people to get where I am. I was expected to achieve in different ways. To make theoretical contributions. To be better at math or business. I was expected to be rich and renowned in my field. I’m not any of those things. I don’t mind that I disappointed people’s visions of me. And yes, I’d love to be rich and renowned. But I’m not and I won’t be.

What I am is a productive, contributing engineer. Mediocre but effective. With other dreams and aspirations now. That are not professionally oriented. Sunday, I compete in a triathlon. I am part of a flourishing relationship. I travel the world. My alcoholism disappointed a lot of people, and derailed my progress toward their goals for me. My recovery has allowed me to focus on what I want to do, what I want to build.

Today, I am a sober member of Alcoholics Anonymous. In 8.5 years of sobriety, I’ve built a life that may not be what I was launched into as a child, but it is one that I can accept for myself. I’m useful. I’m a taxpayer. I am functioning in a society that I no longer feel owes me easy success. I used to take two steps backwards for every step forward. Now, I take two forward for each step back. I’m not perfect. But I’m making progress.

I don’t know how my life is going to proceed. Maybe I change jobs again. Maybe I change careers. Maybe I get injured or sick. Maybe. Maybe.

I’ve disappointed a lot of people. And I think I’ll continue to from time to time. That’s what I’ve had to do to find my own path. Most days it’s a good path. Some days, not so much. But it’s mine. I am its author, and I am its only true reader. I have to be the one who can live with the story it tells. Today, I can live with the story I’m writing.